Table of Contents

開く- Rice Cultivation and the Beginning of Japanese Culture

- Dark period for ruled farmers (Period of manorial System)

- Solidarity of Self-government Organizations, So and the Formation of Water Use Orders (Muromachi Period (1336~1573))

- Agricultural villages with a strong attachment to land and community (Edo Period(1603~1868))

- Modern Capitalism and the Japanese Family System (From Meiji Period (1868~1912) to the Period before the World War II.)

- The Restoration after the War and the Progress of Land Improvement Works (1945~1954)

- Period of High Economic Growth and the Decline of Villages (1955~1964)

- Rural improvement projects to narrow the gap between the urban and the rural areas (1965~)

- From the technology of agricultural and rural engineering to rural improvement technology (Early Heisei Period (1989~2019))

- Decentralization and Integration of Regional Policies (Late Heisei Period (1989~2019) ~ Reiwa Period (2019~))

- Conclusion ~ Beyond the Trajectory of Water, Land and Communities ~

1. Rice Cultivation and the Beginning of Japanese Culture

Humans are considered to have appeared in Japan about a hundred thousand to fifty thousand years ago. From then until the Jomon Period (ca.16,000 ~3,000 BCE) was known as the Paleolithic age. Few settled housing remains have been found from this era and people seemed to have moved around to live by hunting and gathering in this glacial period.

During the Jomon Period, people started farming alongside hunting and gathering, and sedentary settlements were established. Settlements in this period were generally arranged in a semi-circle with an average population of 30 people, with pit dwellings of 4~5 houses surrounding the central open space. Spirituality seems to have been the center of livelihood, with people conducting religious services through animism (worship of spirits) and situating tombs in the central open spaces of the settlements. People during the Jomon period did not have social class separation and lived in cooperation, based on the evidence from the findings at tomb and housing remains.

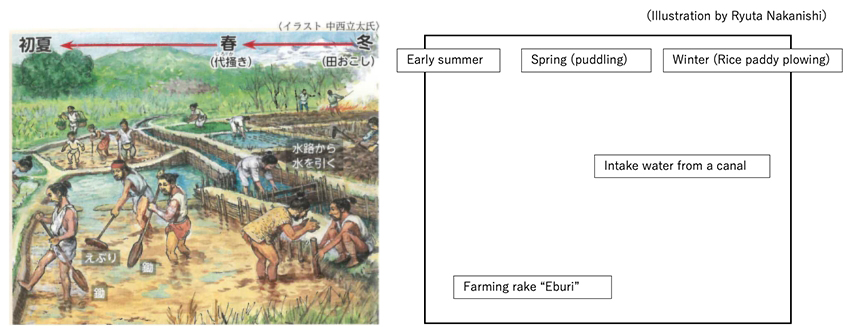

When rice cultivation technology was imported from the Asian continent in the latter Jomon Period ~ Early Yayoi Period (300BCE – 300CE), valleys or low marsh lands were cultivated as paddy fields, which formed the behavioral principle of the Japanese people. The land of Japan was called Toyoashihara Mizuho no Kuni (the land of abundant reed plains and rice fields) in the Kojiki (the Records of Ancient Matters). Rice cultivation needed to be practiced in collective action, which did not allow individual or family related selfish behavior (Figure 1). Blood related groups formed mura (villages), and moated settlements were established by digging moats and constructing earth mounds around them. In the village, rice was stored and collectively managed in storehouses with elevated floors. When rice began to be used as material money, disparities in wealth started to emerge and so did disputes between villages. Livelihood in those days was powerless against natural disasters, and people worshiped ancestors to prevent them. Since around this period, agricultural rituals in each season have become the base of annual livelihood; Minakuchi (paddy sluice) and Otaue (rice planting) festivals in spring (Figure 2), Amagoi (praying for rain) and Hiyorigoi (praying for good weather) in summer, Kaze Matsuri (wind festival) and Shyukaku Sai (harvesting festival, Figure 3) in Autumn and Tauchi (tilling paddy fields) and Shyogatsu (New year) have all been inherited to the present.

(Citation: Zusetsu Nipponshi Tuuran (Overview of Japanese History by Figures), p.30, Teikoku Shoin)

Cheering with Sasara, drum, flute, whistle and hand clapping, and rice planting ladies sing songs. Held on the first Sunday of June –

November 23rd became “Labor Thanksgiving Day” after W.W. II.-

(Citation: Ise-Shima Economic Newspaper Homepage (2016.11.24))

Equipment used in rituals, such as dotaku (bronze, bell-shaped vessel), were made of bronze imported from the Asian continent. Iron was used for not only farming tools but also weapons/defensive armament, thus the group with good access to iron could expand their power. In the late Yayoi Period (ca. 1st century C.E.), the Wano Nakoku (Na State of Japan) emerged as a Kuni (a small state.) In the early 3rd century, the Yamatai koku (kingdom) ruled by the priestess queen Himiko was established with about 30 Kuni under its control. (This information comes from the Gishi Wajin Den (the account of the people of Japan in the history of the Wei Dynasty)).

In the meantime, the Yamato Chotei (Imperial Court), that could even control labor power to construct giant ancient tombs, started to master paddy field development technology (agricultural and rural engineering technology). Large paddy field areas or ‘Kuni no Mahoroba’ (great and splendid land), shining green in summer and gold in autumn, were created in the south-eastern Nara basin (Kojiki). Religion during the Kofun Period (mid of 3rd ~ 7th century) became a primitive form of Shinto based on the ancestor worship of the Yayoi Period (10 century B.C. ~ mid of 3rd century C.E.), and shrines were built to enshrine nature gods, ancestor gods, etc. in each region.

2. Dark period for ruled farmers (Period of manorial System)

Prince Shotoku enacted Jushichijo no Kenpo (a constitution consisting of 17 articles), stating the primitive values of Japan, and made cooperation and harmony national virtues. This can be observed in the ordering of articles within it. Article 1; “harmony is to be valued”, and article 2; imported religion “Buddhism is to be worshiped”, came before article 3; “Imperial commands are to be obeyed”.

When the nation governed by the Ritsuryo codes was established by the Taika Reform in 645, people received allotted paddy fields under the Kouchi Koumin Sei (a system of state-owned land and people), but the livelihood of farmers was very miserable, as described in Hinkyu Mondo Ka (dialogue poem on poverty) in Manyoshu (the oldest anthology of Japanese poems). Before long, allotted paddy fields started to become scarce, and the state allowed the private ownership of newly developed land by enacting the Konden Einen Shizai Act (an act allowing farmers/developers to own cleared land permanently) in 743, which led to the expansion of privately owned lands (manors) by aristocrats and temples/shrines. For about 800 years, from then until the end of the manorial system, a period of competition for the right of taxing manors by aristocrats, temples/shrines and warriors continued. During this period, few provincial governors or manor lords invested in constructing costly water sources or irrigation facilities, and neither population nor agricultural land increased significantly. Manorial farmers could barely live and were not even allowed to construct tombs or hold funerals. They were forced to work cultivating the privately owned land of the lord without having any rights to the agricultural land or means of production and were exploited in many ways because of complicatedly entangled land ownership.

3. Solidarity of Self-government Organizations, So and the Formation of Water Use Orders (Muromachi Period (1336~1573))

In the Muromachi Period, Shugo Daimyo (Japanese territorial lords as provincial constables) deprived the rights of manorial lords, and the status of small and middle size farmers who had been forced to work like slaves improved. This led to the formation of So (rural self-governing organizations), made up of regionally-grouped and naturally-formed settlements as a unit. So established Mura Okite (rules of the village) through yoriai (village assembly), consisting of all community members as a decision-making body, and collectively conducted farming activities, operation and maintenance of irrigation systems and iriaichi (common land) and public security/disaster prevention activities; and sometimes even practiced self-government trials for executing punishments (ex.mura hachibu (village ostracism), etc.). When the ruling class threatened the rights of farmers in an unjust manner, they were confronted by such measures as gouso (direct petition to the lord), chousan (fleeing in a group) and ikki (group uprising with weapons).

Water disputes and disputes over common land frequently occurred between Sos, which were united with strong solidarity. The Takinagawa River in Iwate Prefecture had scarce water resources, and the mainstream and the branch stream were separated into two in front of Shiwa Inari Shrine. When drought continued, farmers on one side of the stream often banded together and closed the water intake of the other stream, resulting in a record number of water disputes 36 times (water disputes of Takinagawa River) during the 300 years from the Edo period (1603~1868) to the Taisho period (1912~1926) (Figure 4). In the dispute of 1865, 2 thousand people from the mainstream side and 3 thousand people from the branch stream side confronted each other, and Tajibei Nomuraya was stabbed to death in the brain with a sickle and Matsuzo was killed by being hit on the head repeatedly with a fire fighter’s hook. In agony, Matsuzo asked for help, but his opponents mercilessly urinated on his face, saying “drink the water of your last moment”1). Long lasting water disputes in this area finished with the construction of the Sannoukai Dam in 1952, and the word “Heian” (peace and security) was written with plants on the dam body and is still maintained.

(Photo taken by:Tohoku Agricultural Administration Office of MAFF)

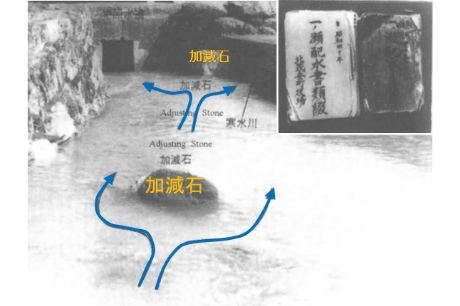

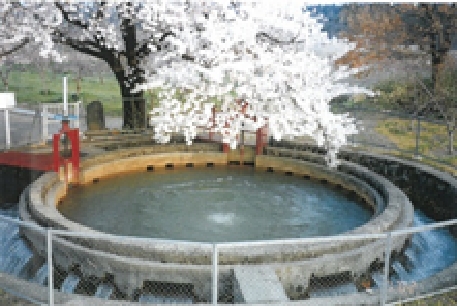

Without water, no food is available. Thus, it literally became “a matter of life and death” for a village to obtain water. In spite of severe water disputes as mentioned above, farmers understood that it would be a loss for all if the whole water system was damaged. Thus, adjustments were repeated at every water dispute, and water use orders were established in everywhere by exchanging signed deeds. In particular, water divisions to allocate intake amounts were of the most important concern for villages. In the Ichinose weir, diversion volume was adjusted by setting two natural stones, called kagen ishi (mimakuri ishi: stones to adjust/allocate water) (Figure 5). Circular tank diversion works (Figure 6) can divide water in a fair way for dissolving water disputes, but have only been used since after the modern period (1914~)2).

(Citation: Daichi eno Kokuin, p.124)

(Photograph by Fukushima City Land Improvement District)

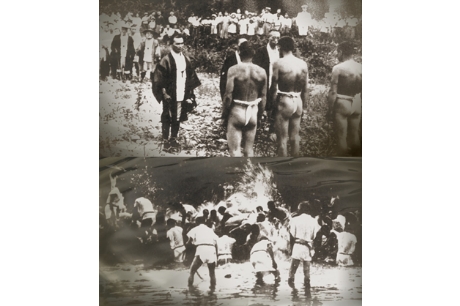

During periods of drought, a rotational water supply was adopted for sharing water equally by dividing times for water intake. In the Sanuki region (Kagawa Prefecture) where rainfall is very scarce, allocation of irrigation pond water was adjusted by the burning duration of incense (Senkou Mizu: incense water) (Figure 7). In the Takatokigawa River, in Shiga Prefecture, the ritual called “Iotoshi” (breaking weir) had been practiced for more than 400 years until 1943, in which farmers of a downstream village wore white clothing and broke down part of a wood pile/sod weir of the upstream village at the time of drought3) (Figure 8). Rice cultivation has been considered a practice with public interests beyond the framework of individual organizations and drawing water for one’s own field has been considered criminal.

(Photograph provided by Tochikairyo Section, Nourin Suisan Division, Kagawa Prefecture)

(Top) Representatives confronted and made a statement before Iotoshi

(Bottom) A ritual based on promises was solemnly practiced respecting the history of blood shed

(Citation: Kohoku no Inori to Nou (Praying and Agriculture in Kohoku) in Suido no Ishizue (Foudation of water and land))

4. Agricultural villages with a strong attachment to land and community (Edo Period(1603~1868))

After Hideyoshi Toyotomi unified Japan to end the Sengoku Period (1467~1590), he confiscated weapons from farmers by katanagari (sword hunts) and prohibited the change of social positions (Heinou Bunri: separation of warriors and farmers). He also initiated Taiko Kenchi (cadastral surveys) to register cultivators of the land (Honbyakusho) to the Kenchi Cho (cadastral book) and obliged farmers to pay annual taxes (Nengu) based on their yields (Kokudaka). After the death of Hideyoshi, Ieyasu Tokugawa controlled land and people with the Bakuhan Taisei (feudal system of the Shogunate and domains). He determined village boundaries (murakiri) taking into account such factors as availability of irrigation water and access rights to common fields/mountains and allocated annual taxes/other contributions using villages as a unit (murauke seido: village contract system). There were about 70 thousand villages in Japan, and 80% of the population were farmers living in them.

A village was mainly managed by Murakata Sanyaku (three key officers of a village): Nanushi (Shoya, Kimoiri) (a village headman), Kumigashira (a group leader) and Hyakusho Dai (a farmer representative). Whole villages cooperatively conducted fire and crime prevention activities, festivals and annual events and bore all their costs, using Gonin Gumi (a five family neighborhood unit) (5~6 land cultivator farmers) as a management unit. Farmers started to have strong attachments to their land after their right to cultivate their land was formally recognized, which allowed them to let the eldest son inherit the land and house. When they developed their land, they dreamed that their descendants could have a better livelihood. As such, new paddy field developments had been promoted.

In Ukiha City, Fukuoka Prefecture, the Go Shoya (five village headmen) made a grand plan of withdrawing water from the very distant Chikugogawa River when their villages were impoverished by water scarcity and appealed to the lord after making a survey by themselves. With cooperation from a county magistrate, the project plan was approved by the domain but only on the condition that the five headmen would be crucified on the construction site if the project failed and that the works proceeded in front of crucifying platforms. After the completion of the Oishi weir in 1674, barren land was turned into an extensive granary, and in later years the Nagano Sui Jinja Shrine (Go Reisha (a five-spirit shrine)) was constructed to worship the Go Shoya.

In Saito City, Miyazaki Prefecture, Kyuemon Kodama, a second son of a village headman, had an idea of withdrawing water from the Hitotsusegawa River to make the village prosper, and initiated an irrigation project with funding from a wealthy merchant while explaining the project plan by visiting house to house. With enormous difficulties, including interference from opponents worrying about flood damage, the weir being washed away by a flood, and having to give up all his private land/house properties after the investor left him, he became penniless yet continued with the work. He finally completed the Sugi Yasui Zeki weir in 1720 after a new investor offered his support. In this way, new paddy field developments progressed rapidly in all parts of Japan by the aforementioned predecessors who devoted themselves to developing their areas. During the 100 years in the early Edo Period, cultivation area in Japan doubled from about 1.5 million ha. to about 3 million ha. Many stories of predecessors in the local areas related to a new paddy field development have been inherited in all parts of Japan.

Many people became victims of construction work related to regulating water by embankments or weirs, so burying people alive in the earth or water bottom had continued until the modern period as a custom of offering human sacrifices to the gods. In Seki Jinja shrine, Fujisaki Town, Aomori Prefecture, Tarozaemon who sacrificed himself and contributed to the weir construction is enshrined as a god, the situation of which is shown in the picture of Figure 9.

(Citation: Website of Tourist Information of Fujisakicho Town, “Fuji Sanpo”)

Local ancestors who developed land and established communities were enshrined by farmers as Ubusuna Gami (a guardian deity of one’s birthplace) or Uji Gami (a tutelary deity) in the Chinju no Mori (forest of the village shrine) and were worshiped for the prosperity of the village. The Shogunate even allowed poor farmers to build tombs with Danka Seido (the system of support by a temple,) and the people prayed for the happiness of their family to the spirits/souls of ancestors who were buried at the tomb of the supporting temple. These temples and shrines functioned as a place of gathering, and through annual events connected deeply with agricultural rituals people enjoyed the seasons, prayed for wishes and strengthened the bonds inside the community. As such, the Japanese started to have a strong attachment to their community with a common fate, including the land which had been obtained by the struggles of their ancestors and the village/domain.

5. Modern Capitalism and the Japanese Family System (From Meiji Period (1868~1912) to the Period before the World War II.)

The Meiji government implemented the Haihan Chiken (abolition of the feudal domains and the establishment of prefectures) in 1871. The government established the Ministry of the Interior in 1873 to consolidate the centralized national system of governance by establishing about 16 thousand cities/towns nationwide using the Sisei/Chouson Sei (municipal administration system) in 1889. Also, Gunze (district policy direction) and Chousonze (town/village policy direction) were the basic plans of action for the new administrative districts established in many places in Japan. In this way, a village during the Edo Period (an old village=a natural village) became an Oaza (a large village section) in a new administrative district of cities/towns/villages and functioned as a village community as seen in water users' associations.

The Meiji government carried out land tax reform (1873~) and recognized the private ownership of land by issuing a land certificate to landowners and owner-cultivators as well as changing the tax payment system from nengu (payment in kind) to a cash payment equivalent to 3% of a land's price. This change contributed to stabilizing the tax revenue of the government, but the land tax was the same even during price declines caused by an abundant crop, a natural disaster, or a poor crop. Thus, many owner-cultivators fell to become tenant farmers because they had to sell their land, handed down from generation to generation, in order to pay the land tax. In 1898 civil law (the Meiji civil law) was enacted to legalize modern land rights such as property rights, farming rights and rights of lease, which led to the establishment of a farming structure where small tenant farmers were exploited by landowners.

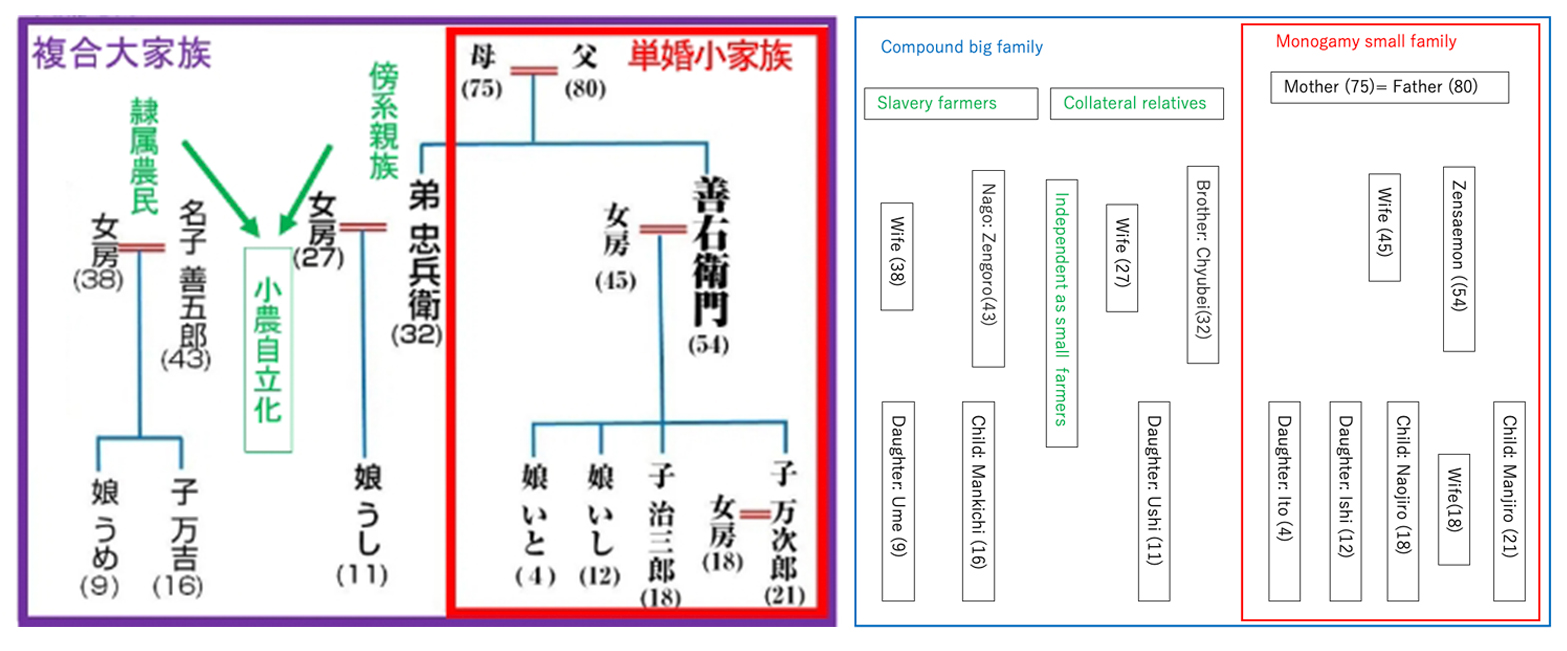

Another characteristic of Meiji civil law was the system of inheritance. Until the Sengoku (Civil War) Period (1467~1590), farmers could only survive by living in large extended family compounds (Figure 10) including extended relatives (couple of second son, etc.) and servant/slave farmers, but during the Edo Period the number of small single families increased because of the progress of Shounou Jiritsu (independent small farmers). During the Meiji period, Uji (a family name) was even given to farmers, and Ie (a family name) along with Uji became a composing unit of the society. Under Meiji civil law, the Koshu (the head of the household) and the other family members had a master-servant relationship. The Koshu had the obligation of supporting his family and was given the Koshu right (the right of the head of the household). The system included Danson Johi (predominance of men over women) and Choushi Yuugu (privileged treatment of the first son), allowing only the first son to inherit all family properties including the land and assets. The grandfather became an Inkyo Mono (a person who withdrew from official household affairs) after he handed over the headship of the family, but for a farming family the grandfather and grandmother were important labor sources, whose wisdom of living, including farming techniques, was indispensable. As depicted in the Kyoiku Chokugo (Imperial Rescript on Education) in 1890, “Be filial to your parents, affectionate to your brothers and sisters and as husbands and wives be harmonious” was considered to be the ideal family image. Thus, a unique Japanese social system of a whole family as a social unit was established in contrast to the unit of a family of husband and wife (nuclear family) in western countries.

(Citation: Professor Hiroomi Baba (Tokai University) Homepage)

Capitalism developed during the Meiji Period (1868~1912) and gave the majority of a village's land ownership to the land-owning class. However a Gounou (a relatively large land owner who not only lent the land to tenant farmers but also cultivated it himself) from the Edo Period and a Tezukuri Jinushi (a landowner who cultivates the land himself utilizing labors of servants or day labors) had the desire of cultivating the land, so they took the leading roles in rural communities by engaging in Denku Kaisei (rice fields revisions) (Figure 11 in Land Chapter) from the early Meiji period to around the Meiji 20s (1887~1896). But after the Meiji 30s (1897~1906) the number of Kisei Jinushi (a parasitic landowner) who depended on farm rentals and Fuzai Jinushi (a nonresident landowner) who lived outside of a village increased, and even though they were active in side businesses such as money lending at an excessive interest rate, they were not involved in community affairs, which resulted in the loss of a sense of village unity.

For about 70 years from the Meiji Reform to the start of the Pacific War, Japan, aiming at Fukoku Kyouhei (increasing the wealth and the military power of the country), had tried to catch up with the great powers of Europe and the United States by shifting from a rice producing country to a manufacturing country. In fact, western countries took 3~4 centuries to achieve economic growth by industrialization, while Japan completed it in less than a century.

Japan faced the Great Depression in 1929 and was hit by extremely poor harvests due to cold damages in 1931 and 1934. Impoverished farmers who could not afford to buy food came out in huge numbers (the agricultural depression of Showa). Undernourished children and the selling of daughters became a social problem, and there were frequent tenancy disputes in which tenant farmers organized themselves into a union to demand the reduction/exemption of farm rent and the improvement of conditions from the landlord.

During this period, the cultivation area expanded but the population also increased. As a result, rice was in chronically short supply, and farmers went abroad to find places for paddy fields. Similar to powerful Western nations, Japan followed the path of expanding its territory, but Japan's ruling policy for overseas territories was different from the colonial policy of western nations.

Hard-working and diligent Japanese farmers developed the land, covered in mud and sweat under the harsh climate of overseas territories. They had to live unstable lives in unfamiliar places and built temples/shrines on developed land to form a community.

The overseas Japanese, living in groups doing paddy field farming, started to develop values similar to those of their homeland through prioritizing the interests of one’s own group rather than private interests, which became a driving force for modernizing Japan in a short period. These values had the aspect of totalitarian ideology that limited individual rights, and sometimes individuals often had to repress their tears for the interests of the group, including the nation, a village, or a family that they belonged to. It was during this time that women often had to marry reluctantly for their families, and many youths lost their lives for their country during World War 2. In the end, Japan was defeated in the war, and became a modern nation of freedom and democracy.

6. The Restoration after the War and the Progress of Land Improvement Works (1945~1954)

In the postwar period, the landlord system was dissolved by land reform (1946~) and principal farmers became owner cultivators (the share of tenant land decreased from 46% to less than 10 %). The Land Improvement Act of 1949 was legalized after the application for the project by owner cultivators (Sanjyo Shikakusha: a person qualified under article 3 of the Land Improvement Act), who led a process of repeated discussions until a consensus was reached. This process played important roles in maintaining and developing the collective working powers of the rural communities. Organizations to coordinate rights and maintain/operate facilities were united into land improvement districts, and prefectural/national federations of land improvement districts were established by the act’s revision in 1957. The Agricultural Cooperative Act in 1947, the Agricultural Committee Act in 1951 and the Agricultural Land Act in 1952 were enacted and the Central Union of Agricultural Cooperatives and the National Chambers of Agriculture were established in 1954 to unify all activities concerned.

During the period of post-war restoration, emergency land reclamation projects were implemented for Kinou Sokusin (which promoted the engagement of soldiers/unemployed persons to farming) and increasing food production. After this, agricultural and rural engineering (land improvement) started to expand their scope of work to include rural planning focusing on subjects such as community planning, public facilities planning and water/sewage planning, in addition to the usual works of irrigation/drainage and agricultural land reclamation. By the enactment of the Comprehensive National Development Act in 1950, the scope of its works expanded to include the development of land and water resources, and social problems such as compensation for land submergence and relocation because of dam construction, the allocation of costs for multipurpose facilities and water use coordination among different users. When Japan entered into a period of high economic growth after 1955, large scale projects including the Aichi Yousui irrigation system, Toyokawa Yousui irrigation system, Hachirogata Land Reclamation (Land Chapter Figure 13) and Shinotsu Peat Land Development were implemented, and land improvements became a comprehensive rural development technology together with the emerging Nougyo Doboku (agricultural and rural engineering) consultants.

7. Period of High Economic Growth and the Decline of Villages (1955~1964)

By 1960 the need for food production increase declined and the program of doubling national income was promoted. To narrow the gap between the farm and industry sectors the Basic Act of Agriculture was enacted in 1961, and such project support systems as the reclamation pilot project (1961) and the land consolidation project (1963) were introduced to promote a labor productivity increase and a selective expansion of agricultural production.

Land consolidation promoted farm mechanization and increased labor productivity, while side job farmers increased as exemplified by the vogue saying San Chan Nougyou (farming by 3 chans; Jii-chan, Baa-chan and kaa-chan) which depended on farming by grandparents and a mother. In rural villages, mixed living between rural and urban residents progressed, and the second and third sons of farm households migrated to cities for employment opportunities.

Former rural residents who started to work in urban companies began to recognize the company organization as a community with a common fate, and they followed the specific behavioral principle of rural residents to realize a remarkable productivity in Japanese companies4). They understood their roles through repeated consultations inside a company similar to a village meeting and pledged their loyalty to the company and held discipline to the end without claiming excessive rights or a wage increase under an enterprise union. Corporate managers also rewarded the service of employees by giving them lifetime employment and seniority-based wages. Corporate managers and employees worked together to expand the market as villages had developed the land to prosper. Founders of large corporations were admired as gods of management similar to the guardian deity of one’s village. Through such Japanese-style management, Japan has achieved a continuous high annual economic growth of over 10% from around 1960 and became the second strongest economic power in the world in 1968.

The standard of living for urban residents has thus been improving rapidly, but in rural areas “hollowing-out of people” (depopulation) in the 1960s, “hollowing-out of land” (increase of abandoned land) in the late half of the 1980s onward and “hollowing-out of villages” (marginalization of settlements) in the 1990s onward have progressed and collective activities of villages have begun to deteriorate due to the degradation of the spirit of mutual help5).

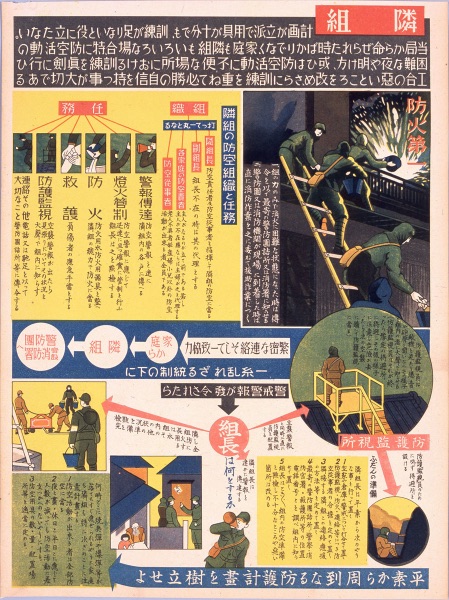

The degradation of feelings of mutual help can be regarded as the reaction of people against repressions by a country, a village, and a family until the pre-war period. Since around the Japan-China war, village or town groups were nationally organized. Under this nationalization existed Tonari Gumi (a neighbor group) (Figure 11). The Tonari Gumi was a keystone of living that distributed such information as a rationing by a Kairan Ban (a circular notice), but it also functioned as a substructure of individual control by the government. After World War 2, town groups etc. were dissolved by the order of the occupation army in 1947 because they supported the war in a grass roots manner. However, the spirit of mutual help in the region was necessary and in spite of the ordinance with punishments, nearly 80% of them were reconstructed with nominal name changes within 3 months of the resolution. The order prohibiting such groups was lifted by the Peace Treaty in 1952, and town groups were revived as Jichi Kai (an autonomous association.)

Tonari Gumi were organized around 10 households as a unit in a town group.

(Provided by:Showa Kan)

After W.W.II, autonomous associations lead diverse local activities including crime prevention, traffic safety control and festival management, however their activities needed to make a clear distinction from those of temples/shrines in the region because of the principles of freedom of religion and the separation of religion and politics in the constitution. The consciousness surrounding the family has also changed. With farm mechanization, opportunities for farming collectively with three generations of parents, children and grandchildren have decreased compared to before, and the second/third sons or daughters after growing up started to migrate to urban areas for convenient living. Furthermore, marriage is no longer a matter of family and society, but an individual matter based only on the mutual consent of both sexes. Then the number of mediators decreased and the cases of late marriage and unmarried people have increased. As a result, nuclear families have increased and become isolated from their local area by the degradation of village communities.

In the end, cases of caring for children by grandparents instead of parents, attending to grandparents at their deathbed, or even taking care of children or the aged by neighbors instead of family members have decreased. Husbands and wives in a nuclear family must give birth to and raise their children without relying on the mutual help of a village community and take care of their aged parents who are living away from the family. The year 1973 is the Fukushi Gannen (the first year of a welfare system) when the present social security system of healthcare and welfare services started. Until now, the declining birth rate and aging population has followed a path of deterioration, and the cost of social security has placed a financial burden on the government (the share of social security cost in the national income stood 0.6% in 1970, but increased to 31% in 2016).

Furthermore, villages drastically changed around 1965 when excessive rice (over production of rice) started to become eminent. Eating rice sufficiently had been the symbol of prosperity for Japanese people, however, when that stage was reached, rice became overproduced and excessive. For a long time, engineers in the field of land improvement have devoted themselves to developing paddy fields by constructing dams and reclaiming marsh lands, but now face new challenges.

8. Rural improvement projects to narrow the gap between the urban and the rural areas (1965~)

After 1965, phrases such as “Balanced development of national land” and “civil minimum” became popular, and narrowing the gap in the living environment between urban and rural areas became an issue. To cope with unregulated land developments (a sprawling phenomenon) for economic development, land use zoning was implemented by legislating the Urban Planning Act in 1968 and the Agriculture Promotion Area Act in 1969. Since rural areas are where agricultural production and rural living are carried out together, the land improvement technology which has been transformed into a comprehensive regional development technology has incorporated rural improvement projects to improve living environment facilities together with production infrastructure. This move was based on the social demands from rural areas nationwide, where the government budget allocation was not enough to fully improve living infrastructures.

In February 1970, “the promotion of a comprehensive agricultural policy” was approved by the cabinet, and the pilot project survey on comprehensive improvements of agricultural infrastructure (Soupa Chosa) was initiated. From 1972, improvements to production infrastructure together with improvements to living infrastructures, such as the creation of housing land for the second/third sons of a farm household, the improvement of community roads and water facilities for farming/drinking/miscellaneous uses, rural sewage facilities, and rural parks became possible by the pilot project on comprehensive improvements to agricultural infrastructure (Soupa Jigyo) with 60% of the national government subsidy.

At the start of Soupa Jigyo, the necessity of enacting the Rural Planning Act for establishing comprehensive rural planning was discussed. More specifically, it was considered that the Agricultural Promotion Act would be integrated with the Rural Planning Act and the Land Improvement Act would be expanded to become the Rural Improvement Act8). However, as a result of coordination between the Ministries of Finance, the Home Affairs and the Construction, the Rural Planning Act proposed by MAFF did not materialize. Concerned ministries agreed that rural improvement would be implemented under the integrated rural improvement plan (a master plan) formulated by municipalities with the guidance of the National Land Agency (established in 1974) through cooperation among concerned ministries. But in the process of coordination among concerned ministries, a memorandum was exchanged that “the master plan does not necessarily determine the plan and the implementation of projects of concerned ministries” and the plan was only partly implemented by the model rural development project (a model project) of MAFF.

The model project covering a small area of an old village was easy to implement compared to Soupa Jigyo projects covering a wide area, and more than 1,300 municipalities (over 40% of municipalities at that time) implemented the project by 1997. In 1970 the wide-area farm road improvement project (Kouiki Noudou: wide-area farming road), and in 1976 the integrated rural infrastructure improvement project (Mini Soupa) covering a settlement of a village were established. In 1983 the rural community sewerage treatment project was separated from Mini Soupa projects. During the -sharp land price rise by the Plan for Remodeling the Japanese Archipelago in 1972, the replotting of non-agricultural land system was expanded by the revision of the Land Improvement Act in the same year to create land for public facilities, including lands for industrial or housing uses and sports parks through the land replotting of a land consolidation project, which enabled an ordered land use by responding to a new land demand in rural areas.

9. From the technology of agricultural and rural engineering to rural improvement technology (Early Heisei Period (1989~2019))

After the start of the Heisei Period, attention was given to fostering farmers as leaders to cope with globalization, together with related measures for less favored areas and conservation of beautiful landscapes and environments. In 1991, two project-support systems were established; the water environment improvement project to construct facilities for landscapes and the ecology conservation and living environment improvement project for rural area vitalization to create land for housing/parks, etc. by integrating scattered farmland conversion demands with the land replotting for new lands. To support these projects, the Advice Center for Rural Environment Support was established, and then the naming of the national government support system for the agricultural infrastructure development project was converted to the agricultural and rural development project.

The concept of a hilly and mountainous area under the law was legally introduced by establishing the support system which included the integrated improvement project for vitalizing rural areas in less favored area (renamed to the integrated improvement project in less favored area in 1995) to promote integrated improvements of a production infrastructure and a living environment in 1990, the farmland environment improvement project to improve the infrastructure covering abandoned farm land in 1992, and the Specific Rural and Mountainous Village Act enacted in 1993. As a result of these actions the share of the rural area development projects in the total agriculture and rural development projects expanded to more than 40% in 1996.

Regional conservation activities by joint efforts of local and urban residents were supported by such non-hardware support systems as the Furusato Mizu to Tsuchi Kikin (a fund for water and land of hometown) in 1993 and the Tanada Kikin (a fund for terraced paddy fields) in 1998. The Japan Groundwork Association was established in 1995 to cope with the conservation and management of rural facilities through the collaboration of local residents, an administration and corporations applying the method of England's groundwork. A rural landscape improvement project was also initiated in 1998 to improve rural areas as eco-museums modeled after the écomusée of France.

The Agricultural Basic Act was changed to the Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas Basic Act in 1999. In January 2001, by the reorganization of the central government (from 23 to 13 ministries and agencies), the Rural Development Bureau was established after transferring affairs under the authority of “the policy proposal and coordination related to rural development across ministries” from the National Land Agency. With these affairs, the Japanese Federation of Agricultural Engineers (established in 1947) was renamed the Japanese Society of Rural Development Engineers in May 2002, and the group of land improvement engineers called themselves the rural development engineers and reaffirmed their determination to contribute to rural development. The public nickname of the Land Improvement District became Midori Net (network of water, land, and community) in 2002 and in 2007 the name of the Japanese Society of Irrigation, Drainage and Reclamation Engineering became the Japanese Society of Irrigation, Drainage and Rural Engineering.

10. Decentralization and Integration of Regional Policies (Late Heisei Period (1989~2019) ~ Reiwa Period (2019~))

Rural development projects have been expanding since the time between 1965 to the early Heisei Period, and have been implemented based on the policy supported by the Rural Development Bureau of the MAFF’s subsidy program. However, because of decentralization (the Reform of the Three Major Policies) after 1998, the delegation of authority from the central government to regional governments progressed rapidly, resulting in the integration of the Rural Development Bureau’s budget into the Grant Program for Improving Rural Areas. This occurred after a budget program screening in 2009 and a major reduction of the land improvement project budget in 2010

To support the maintenance of agricultural production in less favored areas as a non-hardware support system that is closely tied to infrastructure improvement and support for community functions through regional resources conservation activities, the direct payment to farmers in the hilly and mountainous areas through village agreement was established in 2000, and the farmland/water/environment conservation and improvement measure was introduced in 2007. These programs were legalized as a Japanese-type direct payment system (“Japanese-type” comes from the fact that the payment is made to regions and communities but not to individuals). In addition, in view of the shortage of motivated farmers and an urgent need for an income increase, the Rural Development Bureau is in charge of programs that receive close attention from the prime minister’s office including Nou Haku (farm stay) to show the appealing charms of rural areas to tourists, gibier to effectively utilize game birds/animals as local resources that are the source of damage in rural areas, and Nou Fuku Renkei (farming-welfare partnership) to improve employment opportunities and social participation/health for handicapped people in farming.

The Head office for revitalizing town, people and employment was established in the cabinet secretariat in September 2014 and made a basic approach for coping with regional issues, such as a rapid population decrease and aging, by eliminating problems of vertically structured government and working together as one government. To develop rural areas, it is important to effectively utilize a supporting system of various ministries concerned including grant aid related to regional vitalization (the regional vitalization promotion office), local-community vitalization volunteers (the Ministry of Home Affairs), and Chiisana Kyoten (a small base) (the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport). In the basic plan for food, agriculture and rural areas approved by the cabinet in March 2020, “the integration of regional policies” is to be promoted through “the cooperation/collaboration among concerned ministries/agencies, prefectures/municipalities, businesses with MAFF as the center, to grasp the needs of rural areas and solve problems, whiles sitting close to the local area by mobilizing rural development policies altogether.” The integrated improvement project for agriculture and rural areas in less favored area to improve production infrastructures and living environments together was established in 2020 as a subsidy support project in agriculture and rural development projects.

11. Conclusion ~ Beyond the Trajectory of Water, Land and Communities ~

The Japanese who started their group activities with paddy field cultivation had the value of giving priority to benefitting the group they belonged to rather than individual benefits and succeeded in modernizing the country. After W.W.II, the Japanese lost their backbone of “mura” (a community) but devoted themselves to company organizations and made the country into an economic giant. Land improvement engineers in the modern period have coped with various social issues that needed the support of people in rural areas to promote projects and developed their technology into a comprehensive development one for rural areas. To achieve “integration of local policies” from now on, collaboration beyond the barriers of different administrative organizations will be required, as villages established water use systems after experiencing severe water disputes. In the process of coordination and collaboration, the roles of engineering groups that have achieved consensus building in rural areas by coping with substantial issues in the frontlines will become important.

In the frontlines of workplaces, the reduction of overtime work is being promoted under the work-style reform, so rural development workers (national project office, regional development bureau of prefectures, municipalities, land improvement districts, etc.) who are burdened with daily works need to have opportunities to “go out to the site”. Thus partnership among the industry, the government and schools (agricultural and rural engineering consultants and universities, etc.) is important, and the central ministries/agencies and prefectural governments should establish a more simplified system, improve the readability of documents and adopt a simplified approach to the investigation.

Living in a world of information overload, it is important to preserve information relating to the history of water, land and the predecessors who built their foundation in order to pass this on to the next generation. In the new educational course of study, revised after 10 years, from 2020, “traditional culture of the region and the works of predecessors who contributed to the regional development (grade 4 of an elementary school)” and “food production (grade 5 of an elementary school)” will be studied through subjective and interactive deep learning (active learning), so stakeholders of land improvement work in each region are expected to fulfil important roles.

Trajectories that have been drawn by water, land, and community development in the country of abundant rice over 2,000 years have developed and expanded paddy fields through the work of our ancestors and by integrating technology and labor while hoping for the prosperity of descendants of village communities. For the future, it will be necessary to revitalize villages (communities) and then hand them over to the next-generation’s core members in each district and organization by establishing partnership among different interest groups for the whole benefit of the country and improving the production and living infrastructures by concentrating the technology and resources in the present.

Major references

1. Kouhou (public relations magazine) Shiwa. Furusato Monogatari (a story of a home town) 27 (Shiwa Cho homepage)

2. Entou Bunsui Dotto Kom Homepage (circular tank diversion dot com homepage)

3. Terumi Kaneko. Daremoga Shitteiruhazunanoni Daremo Kangaenakatta Nou no Hanashi (Story of agriculture everybody knows but did not ever think), 2007.

4. Akira Takubo. Suiden to Zenpou Kouenfun. (Paddy Fields and Keyhole-shaped Tomb”). Nobunkyo Production, 2018.

5. Tokumi Odagiri. Nouson to Nouson Seisaku no Jittai to Tenbou (Reality and prospects of rural areas and rural policy), Study gathering at MAFF, Nov. 12, 2019.

6. Fukuyama Jichikai Rengoukai Homepage

7. Tochi Kairyou Kensetu Kyoukai (Land Improvement Construction Association). Tokubetu Kikaku Heisei Tochikairyou Kou (Special Issue on Land Improvement Consideration during Heisei Period). Journal of Land Improvement, No.305, 2019.

8. Yohei Sato. Nouson Seibi Sesaku no Ayumi to Nouson Keikaku Kenkyu no Tenkai Houkou (Historical review of rural development policy in Japan and some implications for rural planning studies). Journal of rural planning, Vol. 30, No. 3, 2011.